Every car has a blind spot. An area, usually over your shoulder where the mirrors and your line of sight just can’t quite see. They are the cause of many auto accidents, even for careful drivers. We look over our shoulder, check our mirrors, and change lanes. But hiding in the blind spot is a car we never saw because it was in the one place hidden by the frame of our car that mirrors and windows didn’t give access to. We never even saw the crash coming.

People have blind spots too. Things we don’t recognize because they are too inconvenient or too uncomfortable to acknowledge. Or sometimes things that we don’t notice because our circumstances are privileged enough not to make it a visible problem to us, though it’s obvious to others. Even those of us checking our mirrors diligently, miss it.

I was recently invited to be a part of a group called the “Superintendent’s Key Communicator’s Group” in my local school district. Each school in the district sent several representatives to hear information from the district administrators and become liaisons to other parents and community members.

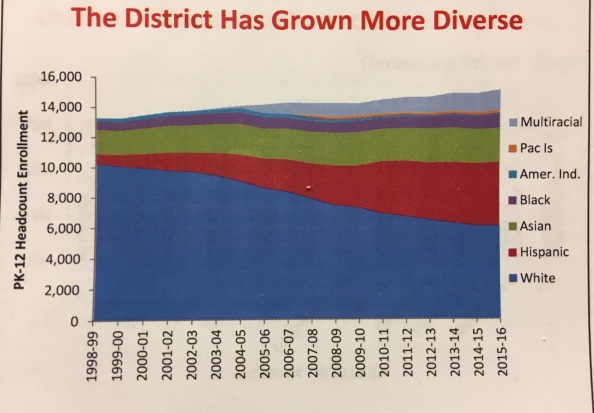

In our first gathering today, the Superintendent laid out the changing demographics of our area. In just 15 short years the racial/ethnic demographics in my community have changed a great deal; from a population that was 76% white to only 42% white. It has become a much more racially diverse community, with Hispanic, Multi-racial, Asian and African-American percentages rising as quickly as the white community has declined.

In the elementary school I was representing, we have changed from 41% non-white population in 2003-04 to 67% non-white population in 2013-14.

And to the credit of the school district administration, they presented this data as an incredible opportunity for our children to learn the cultures, languages and values of different types of people. There was an embrace of this change that I was jealous the church would have for these same sort of statistics.

And to the credit of the school district administration, they presented this data as an incredible opportunity for our children to learn the cultures, languages and values of different types of people. There was an embrace of this change that I was jealous the church would have for these same sort of statistics.

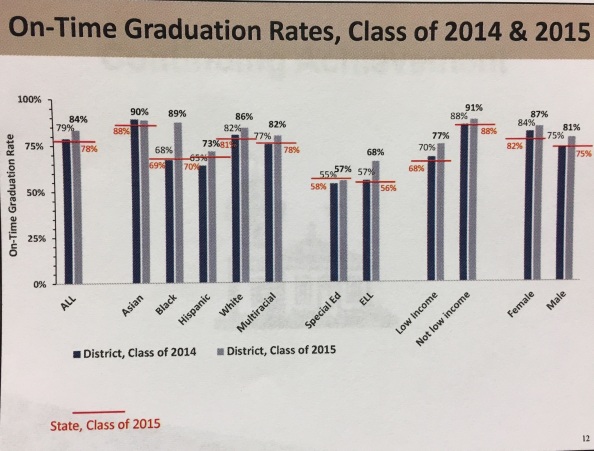

And the data showed that as we had become more diverse, so our schools were doing an even better job of increasing graduation rates for all racial and ethnic population groups.

At the end of the presentation I was feeling a great sense of pride in my community that had not only embraced cultural diversity but had helped elevate the success of white and non-white sub-groups.

It was at this point that the administrators had us turn to someone sitting next to us and discuss our “aha’s” from hearing this data. So I turned to the young, professional lady sitting next to me. We introduced ourselves and shared our thoughts.

I shared first, telling her how I had felt encouraged that the district seemed to value diversity so much and was doing a good job working to ensure that kids in all demographic groups could succeed. I assumed she would say something similar.

But instead, she helped me see my blind spot.

My new friend just had one question based on the data, “Does the staff and administration of this district match the changed demographic of the people being served in this community?”

Hmmmmm….

I looked around the room. From a quick count, I could see that at least ¾ of the room was in the “white” people category. Strange. We were chosen to this group to represent our local school. But if the statistics just given were accurate and people like me, in the “white” category were in the minority, why were we the dominant voice in such an influential group? What about concerns that parents of color might have that I might not understand or be aware of? Why wasn’t a more racially diverse group chosen to more accurately represent the populations of the schools?

Then I thought about how I was invited to this group. This group is invitation-only after all. I was invited by the principal of the school my kids attend. The principal who is also in the “white” category. And now that I think of it, I’d say the vast majority of teachers (all who seem very sweet, well-intentioned and excellent) in our school are notably white. I wondered how many non-white principals there were in the district? How many teachers? Paraeducators?

And as I glanced up from my notes, I took an inventory of the district administrators on hand for this meeting. Most of the major players in the district administration (including the superintendent) were present. And not a one of them was in the non-white category.

Now I want to make sure at this moment to reiterate that I think all the teachers, paraeducators, principals, and district administrators I’ve met are incredibly capable, well-intentioned and caring people. I don’t perceive any intentional slight or prejudice on their part. In fact, they seem to truly value diversity of people and want the best for the community.

But what if they have a blind spot too?

You see the thing about blind spots is that you can’t see them. It’s very hard to recognize them on your own. In fact, as the discrepancy between leadership and population demographics came to my awareness I was shocked I didn’t notice it before. I try to be sensitive to things like this. But I’m not sure I would have seen it had it not been for my new friend sitting beside me.

So, why did she see it?

Well, she’s in the “non-white” category. She saw instantly what the majority of us in the room were blind to. She read the data that she was in the racial majority of the community, but vastly under-represented in this community group, in the hands-on teaching environments of the schools, and in the leadership of the district. She was worried that many of the legitimate concerns of a racially diverse community wouldn’t be addressed or even acknowledged if we don’t have diversity all the way to the top.

And she was right.

If we have a big blind spot in this crucial area, what else are we missing?

What we often forget about “white privilege” in this country is that it doesn’t have to be overtly racist or bad-intentioned. Sometimes people are under-represented not out of a nefarious reason but because we just can’t see our own blind spots.

So, how do we notice the blind spots?

Well, we are going to need people in the “non-white” category to lead us. Those of us in the “white” category need to do a better job of inviting the “non-white” voices into the room and hearing their perspective. We need to allow them to shine the mirror on our blind spots. And then we need the courage to trust it and make changes.

And maybe people like me need to give up our spots on the invite-only superintendents group and make sure more people of color take our place.